Opt-Out Icons and Apple Privacy Labels: The Visual Privacy Policy

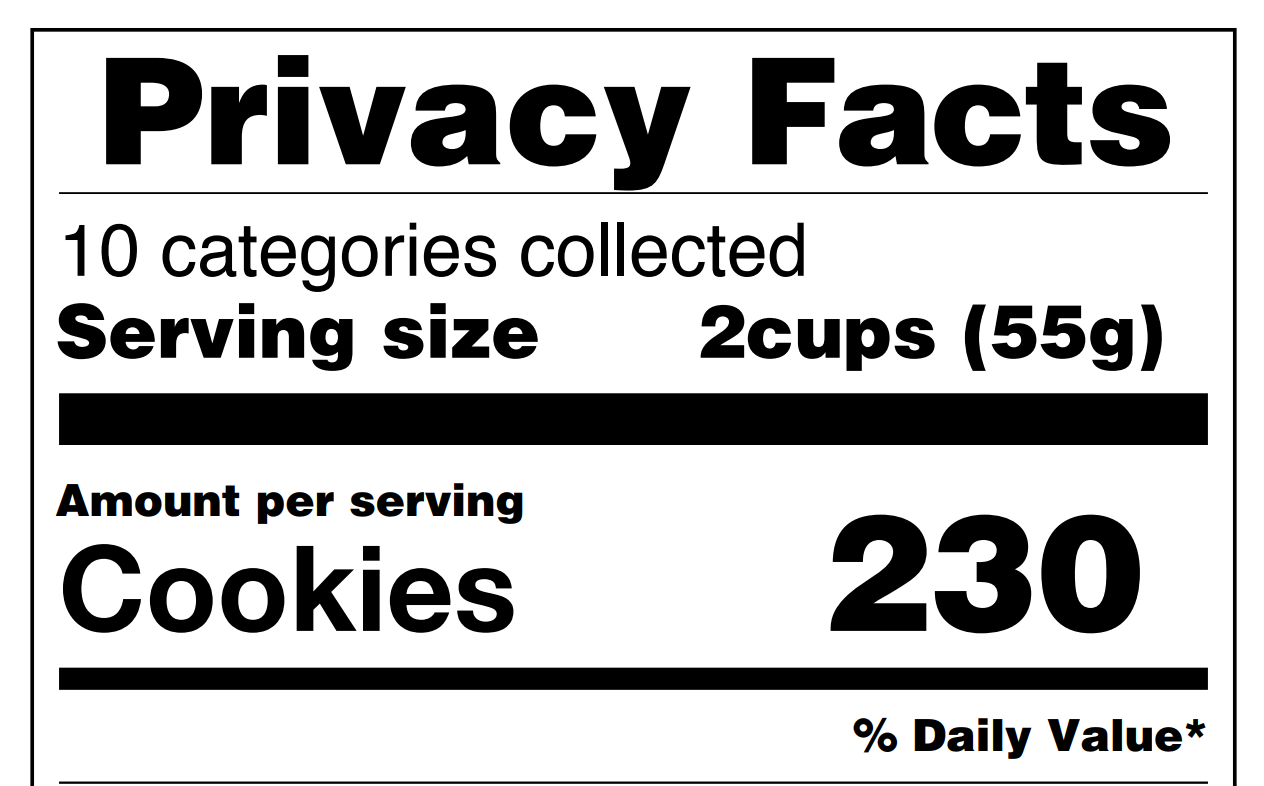

Image Credit: FDA Nutrition Label, modified by Metaverse Law

The growing frequency and severity of privacy incidents within the past decade—the Facebook-Cambridge Analytica data scandal and Equifax data breach, to name just a few—has made consumer privacy a topic of public attention and concern.

In response to consumers’ increased wariness regarding their private data, some companies are trying to use privacy labels and icons to signal a commitment to privacy protection. The ultimate goal is to make privacy more accessible, transparent, and understandable.

This article reviews the history and current trends around privacy icons and labels.

Privacy Visuals Part I: Icons

In 2010, the Digital Advertising Alliance (DAA) rolled out its “YourAdChoices” icon – a clickable blue triangular icon found on ads. This was one of the first privacy icons available. The DAA developed this icon in response to speculated federal regulation in the advertising industry.

To address Congressional inquiries into consumer privacy (and any possible resulting legislative efforts), the DAA formed a self-regulatory program with a set of privacy principles for participating companies and developed the YourAdChoices icon. Participating companies can voluntarily elect to place this symbol on their advertisements. By its nature, the DAA self-regulatory program and use of the YourAdChoices icon is not enforced by law. However, the DAA enforces the program by offering a consumer complaint process, public investigation procedure, and if necessary, escalation to a government agency, which happened in the case of SunTrust Bank in 2014.

Typically, the YourAdChoices icon is placed on cross-context behavioral ads—that is, ads targeted to consumers based on a profile of that consumer’s characteristics, preferences, and internet activity. If a browsing consumer views an ad that was targeted to them, they can click the YourAdChoices icon next to the ad to control whether ads should be personalized to them while browsing and to learn why that certain ad was displayed to them.

When the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA) came into effect in 2020, it created new privacy requirements for over 500,000 business nationwide . One of the requirements is to prominently display a “Do Not Sell My Personal Information” link on a business’ homepage, if a business is subject to CCPA, and “sells” or discloses a consumer’s personal information for valuable consideration. If a consumer submits a request through the link, the business must allow consumers to opt-out of the sale of that consumer’s personal information.

In response to this new requirement, the DAA designed a green version of the YourAdChoices icon for CCPA use. This is called the Privacy Rights Icon.

When implemented correctly by participating companies, the green Privacy Rights icon brings consumers to www.privacyrights.info, a website set up by the DAA to help centralize and facilitate “Do Not Sell” requests across all participating companies.

While the two DAA icons above are forms of industry self-regulation, the California Office of the Attorney General (OAG) has also designed a “Do Not Sell” button to accompany the Do Not Sell link.

The OAG scrapped this design in an earlier set of regulations published on August 14, 2020. See 11 CCR § 999.306(f), Second Modified Regulations. However, in the most recent set of amendments to the CCPA regulations released on March 15, 2021, the OAG published a new design for the opt-out icon.

According to the most recent amendments, the CCPA Opt-Out Icon cannot be used in place of the text link for “Do Not Sell My Personal Information,” but can be used as a visual aid next to the link itself.

Why has the Attorney General refused to use an icon in place of the “Do Not Sell” text link? This is likely due to the fact that, as noted by the New York Times, studies have shown that consumers do not necessarily understand an icon, even if they recognize it. Researchers at Carnegie Mellon University, the University of Michigan, and Fordham University School of Law found that while 14.3 percent of users were familiar with the DAA’s YourAdChoices logo, only 2.9 percent understood what it meant. Due to these findings, the researchers recommended that privacy icons be accompanied by a text description, at least during the phase before broad adoption when consumers are still familiarizing themselves with their legal rights and options.

While privacy icons, buttons, and logos can serve as an effective visual aid, organizations should be careful about making their disclosures too simple by foregoing additional text or explanations to accompany a visual. A company’s good intentions might be misinterpreted, making privacy disclosures harder to comprehend.

Privacy Visuals Part II: Privacy Labels

Many consumers are familiar with the “nutrition facts” labels on food packaging that displays the food’s kilocalories and other nutrient amounts within a specified serving size. These labels were not mandated on most food packages until the Nutrition Labeling and Education Act (NLEA) of 1990, the result of Congressional effort to standardize food labeling and encourage healthy consumer dietary practices. As Dr. Louis W. Sullivan, then Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, stated, “The grocery store has become a Tower of Babel and consumers need to be linguists, scientists and mind readers to understand the many labels they see.”

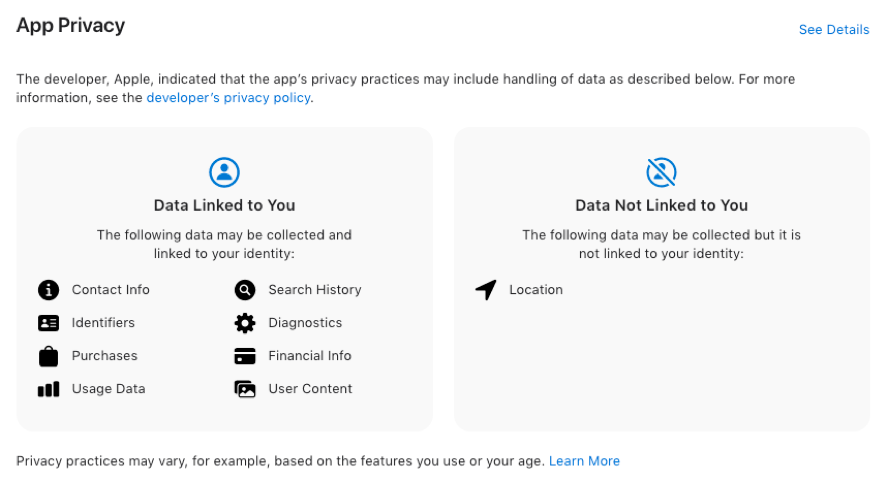

A similar initiative is underway in the privacy arena. On December 14, 2020, Apple required all application developers that publish on Apple’s App Store to include uniform privacy labels, in a format that is easy to read at a glance. The privacy labels list standardized categories of data collected by the application’s developer across three main buckets:

- Data used to track a consumer across different third-party apps or websites;

- Data linked to a consumer’s identity; and

- Data collected but not linked to that consumer’s identity.

These labels, while certainly a welcome step toward improving consumer transparency, have met with criticism. One critique of the Apple privacy labels is that the labels are self-published by the application developer—e.g., Facebook provides the information on its own privacy labels for the Facebook application and Facebook Messenger. Because privacy labels are self-published and not verified independently by Apple, these disclosures may have inaccurate or misleading information.

This situation is similar to website privacy policies, however, which are also self-published policy documents. While website privacy policies are self-published, the policies serve as an enforceable contract between the website operator and the website user. If any statements made under the privacy policy is untrue, it may be the basis for a deceptive trade practice claim under the FTC Act, Section 5. See, e.g., In the Matter of Zoom Video Communications, Inc. In addition, state regulators can investigate and fine businesses for inaccurate or misleading privacy policies under new laws like the CCPA and the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act.

The same may be said of the Apple App Store privacy labels. It is in the developer’s best interest to accurately disclose the categories of information collected or risk a deceptive trade practice claim or regulatory action.

In addition, developers will encounter difficulties synthesizing the information between an application’s posted privacy policy and the Apple App Store privacy label to prevent discrepancies or conflicts. For instance, geolocation data may be linked to user data solely for location-enabled features or options in an application, with consumer consent, yet the Apple privacy label will force developers to disclose this linkage wholesale. Like nutrition labels, a lot of information may get lost in simplification.

The Future of Privacy Disclosures

Privacy policies and other disclosures are an integral part of any organization’s external privacy posture and typically one of the first parts to tackle in a privacy management program. However, wordy and dense policies are commonly criticized as being written by lawyers for other lawyers, not for the everyday consumer.

Many techniques exist for making privacy policies more digestible. Some policies might incorporate a “plain English” paraphrase in the margin next to the actual privacy policy text. Other policies might use bullet point summaries for each section and allow the web user to expand sections to read in further depth if interested.

The use of visual aids such as buttons, logos, and icons can assist the consumer in locating their privacy options. Apple privacy labels are another option that is easy to scan and compare across multiple competing applications, websites, or services. Now that so many options exist for signaling privacy, businesses need to consider how they will showcase their corporate brand and improve the user experience for the new privacy-conscious consumer.